Over the last seven years the Pumas have become, in every sense, a force in world rugby. It is not a feeling or an exaggeration: the numbers show a real rise. Argentina have collected “eighteen wins against nations stably sitting in World Rugby’s top 10 – a figure that matches what they achieved across the entire previous decade”. It is a step-change that shows a system that has started to deliver results consistently.

They recorded victories over South Africa, All Blacks, and Australia during various Rugby Championship campaigns, as well as Italy in friendly match. Between the bronze medal at the Rugby World Cup 2007 and the one at the Rugby World Cup 2023 lies a deep chasm of preparation, organisation and development pathways built from the ground up.

The comparison with Argentina, in truth, is not accidental at all. For years there has been a direct thread – increasingly evident – between Argentine and Italian rugby: just think of the relationship with our franchises, which have welcomed and enhanced several albiceleste players – Albornoz, Carreras and many others. There is also a further element that makes the comparison even more interesting: in Argentina about 25,000,000 people (62% of the country’s total population) can claim Italian ancestry, such as Martin Castrogiovanni. It is not merely demographic: it speaks to a deep historical link, a cultural closeness, and a common base when discussing identity between the two worlds.

So how did Argentina build a rugby union national team this solid and competitive? And, above all: is there something in that journey that can become a useful lesson for Azzurri too?

This article is also available in italiano and español.

The Argentina rugby union team

The roots of this success go back to the 19th century, when many British emigrants reached Argentina in search of new opportunities. Along with their traditions they brought a strange sport played with a ball that bounces unpredictably and, over time, destined to put down deep roots in the country’s elite. Between the 19th and 20th centuries, in fact, the sport was a form of social life inside the younger ranks of the wealthy classes. Joining a university club such as Argentina’s CUBA (Club Universitario de Buenos Aires) was not just a way to play sport, but also a way to prepare for a future role within the country’s ruling class. In recent years, Sebàstian Fuentes, a researcher with the University of Amsterdam’s Globalsport project, has shown how this social division still maps onto the geography of Buenos Aires today.

“The everyday places of members of the most traditional rugby clubs of the Buenos Aires Rugby Union (URBA) are all located along similar linear trajectories. The clubs that dominate the URBA and win most matches in the amateur championship are, in fact, in the Northern Zone. San Isidro [in the city’s northern area] represents a territory of the upper and upper-middle classes, where people choose to live for the high-quality landscape context and for the presumed class homogeneity.”

It was precisely from these contradictions that Argentine rugby launched a deep reform process, where tradition was repositioned inside a more structured and meritocratic system. The Unión Argentina de Rugby (UAR) progressively strengthened a federal model able to spot, develop and support talent along a clear pathway – reducing the weight of social background and increasing that of performance, work ethic and individual growth. Even when classist backlash emerged – as in the case of old social posts by Petti, Socino and Matera, which led to a temporary exclusion from the national team – the movement’s direction remained clear: raising standards not only technically, but culturally too.

Argentina pathway

The development pathway for young players was reorganised in 2019 into a meticulous, progressive system designed to nurture talent without rushing steps. Everything begins with local clubs, which in Argentina are far more than simple teams where you take your first steps. It is there that players absorb club culture, learn belonging and receive a first “identity imprint”: a kind of rugby DNA that, over time, ends up shaping many athletes. On club recommendations, the most promising players are called in by the UAR and directed to one of the regional academies in the country’s main rugby hubs: Buenos Aires, Rosario, Córdoba, Tucumán and Mendoza. Those players who meets federal standards can move to the next tier: one of the 17 national academies, where selection becomes even tighter. The federation selects around a hundred players who are invited to a federal tournament that serves as a true proving ground. This is where the decisive step happens: the best are chosen for the Under-20 national team, the Pumitas.

At senior age, players can make the leap into professional rugby by debuting for one of the Argentine franchises in Super Rugby Americas, the annual 15-a-side competition that brings together professional teams from Argentina (such as Pampas XV, Dogos XV and Tarucas), as well as sides from Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay and the United States of America.

But there is not room for everyone. For this reason many Argentine talents quickly find themselves on European clubs’ radar and take the road of sporting migration. But this is not a damaging dispersion: if the federal system has provided a solid base, the exchange of skills and influences between Argentine and European rugby becomes an added value. One example above all: Argentina’s victory over New Zealand in the Rugby Championship 2025. Argentina fielded a matchday XV made entirely of players under contract with European clubs, a 100% “export” line-up.

Within this framework, the comparison with Italy – again, looking at the two starting XV’s in 2025 – becomes a litmus test. Italy’s side that beat Australia in the Autumn Nations Series had a more hybrid make-up: in the starting XV, 40% were contracted to an Italian franchise (Zebre Parma or Benetton Treviso), while the remaining 60% came from France and England (Top14 and PREM). The point, however, is not to decide whether “abroad” automatically equals quality: it is to understand how much a federation can turn the overseas dimension into a system lever, integrating it consistently into pathways, playing principles and the construction of a shared technical identity.

Argentina have therefore shown that a national team’s strength does not depend on geographic proximity, but on the solidity of the pathway that formed its players and the clarity of the model used to reintegrate them. When the academy pathway is coherent, migration does not scatter: it raises the level. That is where the Argentine case stops being an anomaly and becomes a useful lesson for Italy.

What Italy should learn

From this perspective, Italian rugby should be pleased to see players such as Lucchesi, Riccioni and Fischetti sign for the best clubs on the continent. Tommaso Allan has also spoken publicly in favour of this idea: “Diversity is a strength. I have collected small pieces here and there from every country I have been in and played in: you always learn something from others. It has definitely improved Italian rugby. And it will increasingly be the norm. I’m totally in favour.”

Another case that shows this added value is Edoardo Todaro’s English experience. He arrived in England at fourteen, went through the entire Northampton Saints pathway before becoming a star for the English club. Despite growing as a rugby player in another country, his age-grade journey through Italy’s national ranks allowed him to stay connected with the squad and with the Azzurri identity.

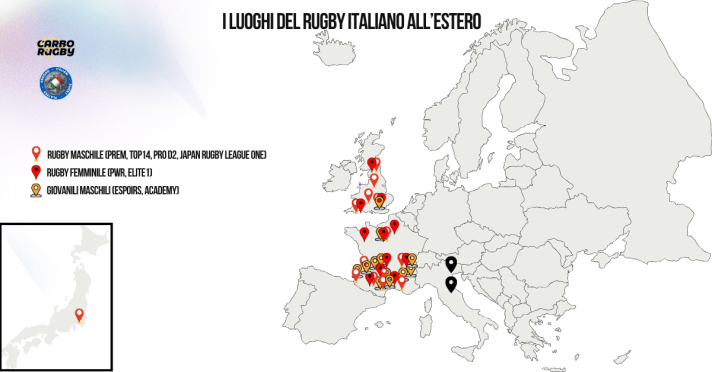

Out of 73 Italian players (men and women) considered – thanks to the invaluable work of the Instagram page Italian Rugby Players Abroad – 82% of our overseas resources are now concentrated in France (19 women, 15 seniors, 26 espoirs).

It is the quality of the link, not geographic proximity, that makes the difference. Seeing Benetton Treviso and Zebre Parma lose some of their best talents should not be read as a loss of quality for the franchises and for our rugby, but as an opportunity: creating space and minutes for prospects such as Leonardo Marin at Treviso and David Odiase at Parma. At the same time, through emigrated talent we can bring back to Italy methods and know-how that will benefit not only the players themselves, but every level of the system.

Alessandro Garbisi

One player who, today more than others, needs minutes – and above all trust – is Alessandro Garbisi. Despite having just renewed until 2028, with Andy Uren (also under contract until 2028) ahead of him in the pecking order and Louis Werchon expected to return in Biancoverde from summer 2026, the available space risks shrinking into a no-man’s-land. At 23 years old it is a dangerous situation, because a scrum-half grows with responsibility, with management, with the repetition of decisions in real matches.

The issue, moreover, is not only about club. If at the 2026 Six Nations Fusco has initially jumped him in the early rotations, the risk of slipping to the margins of the Azzurri picture is not abstract: it is concrete, and it increases every week his rugby lacks a stable rhythm. For this reason, with the aim of regaining continuity and not losing ground in the national team weighing up a new destination – Top 14, Pro D2 or PREM – could be a genuine step forward. Garbisi cannot afford seasons as a bit-part player. He needs matches to run, decisions to make when the ball feels heavy, score and commit mistakes to correct on the road, not mistakes paid as definitive guilt in the eyes of coaches and fans. It is the same mechanism that has made the Argentine model so effective: many talents are developed at home, then find in foreign leagues the ideal context for the final leap, returning to the national team stronger, more mature, more ready. For Garbisi, such a move would not be stepping away from the Azzurri, but investing in his future with the Azzurri.

Conclusion

If Italy want to take a durable step forward, they must stop seeing “abroad” as a place where they hope to fish for players with Italian roots and start treating it for what it can be: a system lever. That means going beyond the Italian Exiles logic – the Federazione Italiana Rugby project designed to identify the best talents aged 17 to 20 with Italian ancestors- and building a broader, structured and stable model of connection with skills and development pathways outside national borders. It is not about abandoning the best, but about building a pathway that develops them well, guides them towards the right choices, and then reintegrates them into the national team within a shared technical model, with clear objectives and, above all, real minutes in their legs. In this perspective, franchises must become accelerators, not parking lots: places that develop and launch, also ready to let some talents go when the next step requires more competitive contexts. But for this to work, you need a director: the federation must be the glue that turns different experiences into a common identity, ensuring technical continuity, monitoring, load management and a structured dialogue with overseas clubs. In an increasingly global rugby landscape, the real question is not whether our players should leave, but whether we are mature enough to help them leave well and bring them back better. Because talent held back by fear – or ego – eventually fades; talent released within a coherent vision, instead, grows. Only then might Mitch Lamaro’s dream of winning the Six Nations become a concrete possibility.

Carborugby is a project shared by a group of passionate fans who aim to create content across blogs, social media, fantasy rugby, and podcasts. If you like our work and want to support the project, you can share our articles and post or buying us a coffee at the link coff.ee/carborugby. We are also translating our articles into English and Spanish to connect with rugby fans all around the world.